Quite a few structures, including the Indenhofen house and farm, where already here in Skippack when George Washington and his Continental Army positioned themselves in the region before and after the important Battle of Germantown.

Just about two years after forming a new army and one year after Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence George Washington led the Continental Army through the Skippack Region on the way to the Battle of Germantown and in retreat just after losing the battle to the British.

In a letter to Thomas McKean, esq. on October 10, 1777 while at camp near Skippack, George Washington expressed his disappointment in the defeat at Germantown writing “If the uncommon fogginess of the morning and the Smoke had not hindered us from seeing our advantage, I am convinced it would have ended in a complete Victory.”

In 1777, at this point in the War, the British held the City of Philadelphia after defeating the Continental Army at Brandywine, surprising General Wayne’s troops at Paoli, and faking a move towards Washington’s military stores in Reading. This feint towards Reading caused Washington to move northwest choosing to protect his military stockpiles rather than Philadelphia. This left a clear opening for General Howe to move his troops across the Schuylkill River near Norristown and on to Germantown before taking the capital city Philadelphia on September 26, 1777.

Researched and written by Mike Dickey

Member of Skippack Historical Society

In early September of 1777, before the Battle of Germantown, there was the Battle of Brandywine in Chester County, Pa. At the Battle of Brandywine, Sir William Howe of the British Army was able to take the upper-hand and defeat General Washington’s army. Due to Sir Howe’s maneuvers, the British then took control of Philadelphia. Washington was criticized for his command capabilities in the field. The General began to plan his next assault on the British, to attack their front line in Germantown, a settlement near Philadelphia. ‘In 1777, Germantown was but a single street extending along 2 miles of the Germantown Road’, writes Edward S. Gifford, Jr. in “The American Revolution in the Delaware Valley”. (qtd in Kennedy) Washington’s army included 8,000 regular Continental soldiers who were recently joined by 3,000 state militia. Conferring with his Generals, they were against an immediate attack, preferring to move the army closer to Germantown and wait for opportune events. (Kennedy)

The army’s move into Montgomery County took them through Trappe, after crossing the Schuylkill River at Parker’s Ford. The army marched by the Augustus Lutheran church where the Reverend Henry Muhlenberg wrote that the men appeared in ‘wretched condition’, noting that the hungry soldiers were short of supplies, “their uniforms worn, and over 1,000 men were barefooted.” (qtd in Mehling, Washington’s) After an encampment in the Collegeville area and another at Pottsgrove, the army made their next encampment near Schwenksville at Pennypacker’s Mill.

On September 28, 1777, seventeen days after the Battle of Brandywine, Washington wrote to Congress from his headquarters at Pennypacker’s Mill, telling them he was ready to move against Howe. (Kennedy) The army camped here from September 26th to the 29th.

The General’s correspondence tells us that ‘Commander-in-Chief (Washington) moved the army on September 29 from Pennypacker’s Mill to the crossing of “Shippack Creek” on the road of the same name’, states Douglas South Freeman, author of “George Washington”. (qtd in Acanthus Group, George, 11) At Skippack, he made his headquarters at the Joseph Smith farm, September 29 to October 2, 1777. After the encampment at Skippack, the army moved to the Methacton Hills area in Worcester Twp., on October 2. There, Washington learned from his spies that the British reduced forces at Germantown to protect a supply column coming up from the south. British forces at Germantown numbered 9,000 approximately. (Kennedy)

Washington’s staff agreed it was time to attack. His strategy was a form of “double envelopment attack” which Hannibal of Carthage used to destroy the Roman legions at the Battle of Cannae, wrote Robert Leckie in “George Washington’s War”. (qtd in Kennedy) It involves a night march of four columns of troops spread over 14 miles, ending in a coordinated attack. Their object was to push the British back, towards the east, to then be surrounded by the flanking militias. The army left Worcester on the night of October 3rd to march to Germantown.

His staff included: Gen. Armstrong who led the Pa. Militia down Ridge Pike, Gens. Forman and William Smallwood leading the New Jersey and Maryland Militias down York Rd., Gens. Thomas Conway, John Sullivan, Anthony Wayne leading divisions down Germantown Pike, and Gens. Nathaniel Greene and Adam Stephen leading divisions down Morris Rd. (Kennedy)

It was about 7pm that Washington’s four columns marched into Germantown. At dawn the next day the army come upon British pickets. Shots were fired, but that morning there was a heavy fog making it hard to recognize enemy or friend. (Kennedy)

The ensuing battle saw Washington’s forces push back the British, past the Chew mansion, except for a British unit of 120 infantry that barricaded themselves in the house and continued firing. However, Washington made the unfortunate decision to allow only the divisions of Gens. Sullivan and Wayne to continue pushing the British farther down the road, while he stopped the remainder of the column to take out the British unit in the Chew mansion. This was a turning point that gave the British a chance to take the upper-hand. They received reinforcements from the east and the battle began to turn as they started to push back Gens. Sullivan and Wayne, who then retreated, running low on ammunition. The unit barricaded in the Chew house was then saved by the advancing British. (Kennedy)

Washington then ordered a retreat that took the entire army back to Pennypacker’s Mill, as noted in the Sullivan Papers. (qtd in Acanthus Group, Sullivan, 11) They were pursued as far as Blue Bell by the British cavalry. The author Robert Leckie reports British casualties at 70 killed, 420 wounded. Washington’s army had a loss of 152 killed, 521 wounded and 400 captured. (qtd in Kennedy)

Grave markers of soldiers can still be seen at Pennypacker’s Mill and at St. James cemetery in Evansburg. St. James, Augustus Lutheran in Trappe, St. John’s Lutheran church near Center Square, founded 1769, and further west, the Bethel Methodist church, built 1770, “served as military hospitals (for the retreating soldiers) when the army was in the neighborhood and at each place men died from wounds received in the Battle of Germantown, according to tradition.” (Skippack Pike Glorified By Washington’s Marching Hereos)

According to author John Watson, ‘General Nash, of North Carolina, Col. Boyd, Major White, of Philadelphia, aid to Sullivan, and another officer, who were among the wounded, were carried onward (from Germantown) so far as that when they died they were all buried side by side, at the Mennonite burying ground and church in Towamencin’, along Forty Foot Rd. (qtd in Acanthus Group, Annals, 12)

The army then camped at Pennypacker’s Mill from October 4th to the 8th. Apparently the troops retreated to the east bank of the Perkiomen Creek, as lieutenant James McMichael wrote in his journal October 5th that, ‘today we changed our encampment to the west bank of the Perkiomen.’ (qtd in Mehling, Historians) This tactical move may have seen Washington stay at the Henry Keeley farm, on the hill to the west of Pennypacker’s, which was also a headquarters location according to the History of Montgomery County, published 1884. Then, on October 8th the army marched to Towamencin Twp. and encamped there. The army returned to Worcester on October 16th , with the headquarters at the Peter Wentz farm, until moving to Whitpain on October 21st.

In the vicinity of Broad Axe, Whitpain Twp., the army was encamped from October 21 to November 2, 1777, on both sides of the Skippack road. The headquarters here was about a mile north at a home on Lewis Lane, called Dawesfield. Father east, in November and December 1777, for six weeks, the Pennsylvania Militia was camped at Militia Hill, in Whitemarsh, while the Continental army was camped in the area to the north of Skippack Road. (Skippack Pike Glorified By Washington’s Marching Hereos) Later, in December, the army made its way to Valley Forge, camping there until June 1778. The Revolutionary War went on for 5 more years, ending on September 3, 1783.

Researched and written by Mike Dickey

Member of Skippack Historical Society

Through the early to mid 1700’s, the majority of Skippack Township was being settled by German speaking families. During the Revolution, the language being spoken in Skippack was still German, as it was through the mid 1800’s. Former longtime resident Eva Boswell wrote of a historian named Bancroft who noted, “although the Germans constituted only 1/12th of the population of the colonies, they formed 1/8th of the patriot army”. (7)

On seven occasions General Washington and the Continental Army camped along Skippack Pike. Three times the army passed through Skippack. The first was to arrive here, on September 29, 1777, after camping at Pennypacker’s Mill near Schwenksville. The second was during the retreat after the Battle of Germantown, October 4, 1777. The third was the army’s movement, on October 8th, from Pennypacker’s Mill to an encampment near the Towamencin Mennonite meetinghouse on Forty Foot Rd.

A stone at Pennypacker’s Mill tells of the army’s encampment here, September 26 to 29, 1777, and then October 4 to 8, on retreat from the Battle of Germantown. The mill property is located in what was then the western region of Skippack Twp. (Skippack was also known as “Skippack and Perkiomen Twp.”, or just “Perkiomen”) Today, at Pennypacker’s Mill is a house-museum of the former Governor of Pennsylvania, Samuel Pennypacker, of the early 1900’s.

In the collection, at the Pennypacker Mansion, is a family Bible with an interesting entry written in German which gives us an idea of the state of the troops, starving and short of supplies. The entry reads, ‘On the 26th day of September, 1777, an army of 30,000 men encamped in Skippack Township, burned all the fences, carried away all the fodder, hay, oats and wheat, and took their departure the 8th day of October, 1777, written for those who come after me, by Samuel Pennybecker.” (Mehling, Historians) Records indicate the actual number of men to be 8,000 of the Continental Army plus 3,000 militia of various States. A soldier, Timothy Pickering, wrote that ‘before dark on the first day of camp every fence on Samuel Pennybacker’s place had disappeared’, as soldiers used all the wood for their fires, despite General Washington’s orders to stop the theft and plundering of local farms. (qtd in Mehling, Washington’s)

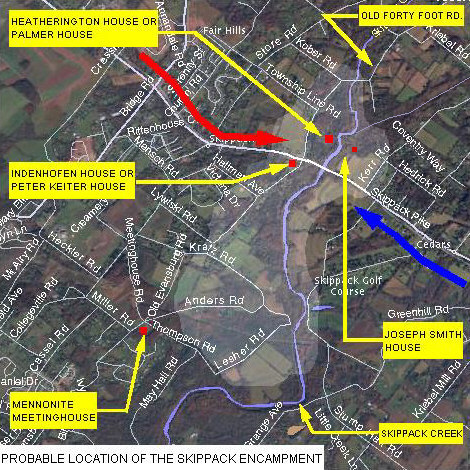

In Skippack, General Washington’s daily expense account records list that he was at the Joseph Smith house, on October 2, 1777, located near the Skippack Creek just north of Skippack Pike. His stay was from September 29 to October 2, 1777. The encampment took place on the land along Old Forty Foot Rd. in the vicinity of the Smith house, and spread to the west and south. Revolutionary War artifacts were found to the western side of the creek, near Old Forty Foot Rd.

To further support the army’s presence in Skippack, there was an advertisement placed by General Nathanial Greene, dated September 30, 1777. It reads, “Headquarters Skippack, 30 September 1777. General Greene lost at North Hanover Camp, a brass pistol, both stock and barrel mark’d H.K. Any person who has found it and will return it to the General shall receive $20.” H.K. infers that the pistol may have been a gift to the General from Henry Knox. (qtd in Acanthus Group, Papers, 12)

About the end of September, the autumn foliage around Skippack is full of color. On September 29, 1777, the army marched down the road from Pennypacker’s Mill and through Skippackville, passing a dozen or so farmhouses and one or two stores and taverns. The mill, built by Gerhard Indenhofen, was operating along the Skippack, at that time. It must all have been a welcoming site for the hungry and wounded soldiers. (Boswell, 7)

“Despite the shortages, the army did receive a good supply of bread while camped at Skippack. Brick ovens were quickly built and flour gathered from the nearby farmers.” (Mehling, Washington’s)

According to Boswell, “it was said within a fifty mile radius, all farms were stripped clean of cattle, feed, fuel, and other materials necessary for the army.” (7) After the Battle of Germantown, hundreds of sick and wounded soldiers returned to the area. Boswell adds, “there can be no doubt that the little community (Skippack) did all possible to feed and help the brave army.” (ibid)

We find this following example of Skippack’s kindness that appears to involve the Indenhofen house and perhaps the owner at the time, Peter Keiter, grandson of Gerhard Indenhofen. The author John Watson wrote in 1877, ‘I have learned from the sons of one DeHaven (later derivation of Indenhofen) that the father had assisted in carrying General Nash, who was brought into his house and then taken two miles further to his brother’s house where he died, having in his profuse bleeding for his country’s good, bled through two feather beds before he died.’ (qtd in Acanthus Group, Annals, 12-13) This indicates the possibility that General Nash was carried into the Indenhofen house, then carried along Forty Foot Rd. to his brother’s home in Towamencin.

One of the most detailed accounts of the army’s maneuvers was kept in a journal by James McMichael, a lieutenant in the regiment commanded by Col. John Bull. McMichael wrote, ‘at 8 a.m. we marched from our camp, passed Penybacker’s Mill and along the Skippack Road.’ (qtd in Mehling, Historians) This movement saw the army pass once again through Skippack, and along Forty Foot Rd. to Towamencin, never again to return.

Researched and written by Mike Dickey

Historian, Skippack Historical Society

The encampment of an army that included some 11,000 Continental soldiers and Militia would have covered quite a large area of land. For comparison, the Valley Forge Park office informs that most all of its +3,300 acres was used in the encampment of Washington’s army, December 1777 to June 1778. Approximately, the army was spread from Forty Foot Rd. and Kober Rd., south towards Thompson Rd. and Mayhall Rd., as the “Papers of General Nathanial Greene” states the belief that troops were also encamped near the Mennonite church until October 2nd, on the west side of the Skippack Creek. (qtd in Acanthus Group, Papers, 12) As Forty Foot Rd. is not too far from the creek, it is almost definite that the encampment included land to the west side of that road.

During encampments, it is reasonable to believe that the army set up camp away from the creek, so as not to contaminate their water supply. With 11,000 troops, undoubtedly there were sick and wounded among them. Land where the encampments took place can also contain graves of soldiers, long forgotten and unmarked. For example, graves of soldiers are found at the site of the Pennypacker’s Mill encampment.

As mentioned in a previous section, the Joseph Smith house was noted as being Washington’s headquarters at Skippack. The Smith farm was located along the east side of Skippack Creek, between Skippack Pike and Hedrick Rd. However, a long time tradition in this area believes that the “Palmer house” was used as his headquarters. It is most probable that it did play some role in the encampment. Below, will be evidence that the headquarters house was more likely on the neighboring Joseph Smith farm to the east of the Palmer property, across the Skippack Creek and also owned by the Park.

The highlighted area shows the approximate area that Washington’s Army encamped in the Fall of 1777. The red line and arrow represent the movement of the troops southeast along the Skippack Road into Skippack from Pennypacker Mills. The blue line and arrow represent the movement of the troops back northwest after the Battle of Germantown. (Map created by Bradley S. DeForest.)

The Palmer property was located along Forty Foot Rd., on the west side of the Skippack Creek, bordered by the road and the creek. The home is known as the “Palmer house” by locals because of the family’s residency through much of the 1900’s. The house is yet standing but has fallen into neglect. It is owned by the Evansburg State Park, listed as the “Heatherington house”.

The Palmer house has its origins from the first settlers, Dirick and William Renberg (brothers). The Rembergs purchased 300 acres from Mathias Van Bebber in 1706. Heckler writes, “on November 1, 1721, the Renbergs sold to George Merckle (Markley), a plantation of 150 acres”. A plantation applied to land that was planted or plantable, inferring that a dwelling was in existence. The land extended eastward from Forty Foot Rd. Heckler states that Merckle later “sold off all his land excepting a small farm of 20 acres with the tenement, and made his will dated May 10, 1762.” It is believed that the tenement was situated at the farm’s edge, being a corner boundary, at NE corner of Forty Foot Rd. & 73. It was originally a stone house of one room downstairs with a room above. (Torn down for a dentist office.)

The original Renberg or Merckle farmhouse appears to have had two rooms downstairs and two above, as noted on a past inspection by the writer, and confirmed by Mary Gehman who was a Palmer and grew up in this house. The house has an addition to the northern gable end that may have doubled its size. Author James Heckler refers to a date stone “D. & H. A.”, David & Helena Allebach, owners from 1798 to 1836. At the time of Washington’s encampment, the farm was owned by Jacob Godshalk of Lower Salford who purchased the farm of 22 acres, on March 1, 1774. His will was dated October 22, 1781, selling it to his only son Godshalk Godshalk. (Heckler)

Located in close proximity, this Palmer house and the Joseph Smith house were in plain view and earshot of the other. Given the number of Generals on Washington’s staff, the Palmer house most likely played host to one or more of them.

The Palmer family had noted the Revolutionary artifacts found on their property, including a sword. The items found here further indicate and support the location of the encampment along the western side of the Skippack Creek.

To give further support to Washington’s headquarters at Skippack, we review the 1936 writings of B. Witman Dambly, an older, long time resident and publisher of the former Skippack newspaper, the “Montgomery Transcript”. Here, the use of the Joseph Smith home is discussed.

Mr. Dambly gives us an accounting from descendents of the Joseph Smith family about revolutionary times. He wrote,

“Before I was born, a Johnson family, sturdy people, known for their native intelligence and patriotism, lived on the 45 acre farm on Skippack Road where stands the 24th milestone (near Kerr Rd). I first learned to know the Johnsons after their removal from that farm. Elizabeth, married to a Fuss and later to a Hallman, was born on that farm February 1, 1820 and died at Lansdale, in 1917. Her parents had told her that the children went from their house, through their own field, to Skippack Road where the milestone stands, to see the soldiers going up and down the road. Elizabeth and other members of the Johnson family agreed that on one occasion several sick soldiers were lying on the bank at the roadside near the milestone. Here, an old lane leads to the farm buildings. (this lane is partially visible today, only the section near where it meets Skippack Pike, being lined with a stand of trees) The patriotic mother (a Johnson) came out to the road with soup and other food for the sick men. Another version is that the Johnson family took the sick soldiers to their house and nursed them until well enough to join the rest of the army.” (Dambly)

Dambly explains that the rest of the story was discovered as a result of a celebration in 1927, the year of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Germantown. A member of a society in Germantown asked, “Who was Joseph Smith?” Here, the Montgomery Transcript used its columns to ask the same question of its readers. An answer was received by Robert B. Souder of Souderton whose father, Jacob G., used to farm part of the of the headquarters farm up until the early 1920’s. Mr. Souder had a number of old papers including a draft of a farm owned by Joseph Smith prior to the Revolution. The draft was made in 1775 for Joseph Smith by David Schultz, a Schwenkfelder from East Greenville area, who was a widely known and respected surveyor. The draft is of a farm having 127 acres and one set of buildings. “The tract had a frontage of more than 4000 feet on Skippack Road…it had a uniform depth of 1280 feet.” The farm must have extended from the center of the Skippack Creek towards the township line near Cedars, and possibly included parts of the south side of Skippack Pike, given the 7 property owners of the farm after being divided. Names include Bean, Wilkie, Cassel, Kerr, Kulp, Speller, and Kulka. At the time of his writing, the owner was Francis F. Kulp, of a farm reduced to 45 acres. Dambly writes that “a public road (Kerr Rd.) has been cut through the farm from Skippack Road, near the milestone, in an easterly direction to the Towamencin line. The length of this cross-road is about ¼ of a mile.” The map of 1893 shows the owner as “W.J. Fuss, 46 acres” which extended to Kerr Rd., and “John P. Detwiler, 39 acres” on the east side of Kerr Rd.

It is likely that Joseph Smith purchased his 127 acres from George Merckle (Markley) prior to 1762. The Merckle farm of 150 acres extended east from Forty Foot Rd. Merckle had sold off land from his farm, ending up with 20 acres, house and tenement, as Heckler indicated.

“The 1766 assessor’s list of Skippack Township contains the name of Joseph Smith, Sr., tailor. His children were Jacob, Henry, Joseph, Katherine, and John. Joseph Smith, Sr. died August 8, 1782 at age 76 years, and is buried at the Lower Skippack Mennonite cemetery.” (Dambly)

Joseph Smith had two sons enlisted in the war. Dambly suggests “this may be the reason for Washington choosing the Smith home as his headquarters. (He probably felt assured that the Smith family was in support of the Revolution, not every family was in favor of it.) Joseph’s son, John Smith, was captain of a company of militia from the region of Skippack. Captain Smith was killed or wounded in the Battle of Germantown. His other son, Joseph, served in the regiment of the Pennsylvania artillery commanded by Colonel John Fyre, and was taken prisoner at the Battle of Germantown.”

Dambly wrote that the Joseph Smith house was of stone, “plastered during the recollection of the oldest residents…there was a date stone, covered over. From several sources, I have it that the house was built between 1700 and 1800. All agree that it is the same house that stood when Washington was there. Descendants of the two former owners of the farm inform me that the house had one-story frame addition; that this frame part was moved about a hundred feet and placed over a walled-up spring and that Washington occupied that springhouse as well. In another location, not far from the house, stood a log house that is still well remembered by the oldest residents with whom I recently spoke.” He also mentions the close proximity to the creek as being favorable to Washington. (It had been thought by others that Washington may have favored his headquarters to be on the opposite side of a creek from his army. At Pennypacker’s Mill it is argued that the headquarters house was on the west side of the Perkiomen Creek, while his army camped at Pennypacker’s on the east side.)

Dambly includes this supporting data from “Washington’s account books, as annotated by John C. Fitzpatrick, Assistant Chief of the manuscript division of the Library of Congress, a trustworthy source, furnishing the link that connects the entire story and removes all doubt of its authenticity. These records say that on October 2, 1777, Washington paid Joseph Smith 2 pounds and 15 shillings ‘for use of house and trouble caused’ while quartered there. Under the same date, there is the record of an additional payment made to Joseph Smith of 11 pounds, 19 shillings and 6 pence for sundries – evidently supplies of various kinds.” At this time, we can not say if there are more entries related to the Skippack encampment that might include other houses, etc. Dambly mentioned that Washington died three years short of time allotted to man, and twenty-two years after the army encamped at Skippack.

He adds, “the headquarters tract was marked by three signs and a flag when the pilgrimage was made during the Germantown Anniversary celebration, October 1, 1927.”

The headquarters home on the Joseph Smith farm was included in the purchase of Evansburg State Park. It was demolished in the mid 1970’s.